After 17 years, I've left the Urbit project.

I've resigned as CTO, board member, and voting shareholder of Tlon (Urbit's corporate sponsor). I've also reassigned my personal galaxies to urbit.org↗ (Urbit's embryonic foundation, still in Tlon's custody).

My family still has a few thousand Urbit stars (in long timelock contracts), plus a nonvoting minority in Tlon. This isn't authority, just compensation: I have zero central power over either Urbit or Tlon. Nor will I contribute code to Urbit, nor write nor speak publicly about it. I am actually done here.

From the very start, I knew Urbit could not succeed until it ceased to be mine and became the world's. Urbit works; its PKI is on the Ethereum mainnet; it's open source; in every way, technical, legal, and mathematical, it is the world's.

(What is Urbit? Please read the primer.)

Let's talk about: why I've left; the state of Tlon; and the state of Urbit. If there's any time left, we'll read some poetry.

Why I left

No one had the power to fire me. (If anyone wanted to, they kept it to themselves.) I wanted to quit; I could; I should have; I did.

I'm a thinker, not a doer; an explorer, not a leader; an author, not a maintainer. My goal was always to fire myself at the first possible opportunity. I'm super happy to reach it.

Any creator is a sort of parent – where control is dependence, powerlessness is independence, and independence is victory. There are a lot of ways to light a fire. The last step is just getting out of the way – which must be done not too late, not too soon, and just right. No one can beat Satoshi in this act; anyone should be delighted to follow him.

I worked full-time on Urbit, alone and self-funded, for eleven years. From 2002 to 2013, I wrote an end-to-end clean-slate system-software stack: an axiomatic interpreter that fits on a T-shirt, a typed functional language that doesn't use abstract math, and a purely functional operating system. I didn't patent any of this; I put it all in the public domain. (Not a valid open-source license; Urbit is now MIT licensed.)

By 2013 I had a stack that worked well enough to make a video↗, then raise a 1.5M seed round. Urbit in 2013 was a working product – in fact, Urbit has had a live global network since November 2013. But in a new platform, the distance between working and compelling is nontrivial. Especially for a seed company with just a few young engineers, building something like nothing ever built before.

Urbit in 2013 had roughly the same feature set as Slack in 2013, but less polished, and decentralized. It was pretty buggy and slow. But had we put all our resources into debugging and optimization, it would not have taken five years.

My instinct was always that Urbit's delivery schedule should be as long as possible. For me, there are always two Urbits: the Urbit that exists, and the Urbit that should exist. To invent the latter I have to inhabit it. When I look at the present, I try as hard as possible to look at it from the perspective of the future – that's where my head should be.

This always makes me think Urbit sucks. And the last thing you want to do is evangelize anything that sucks. This is a bias, but that doesn't make it wrong. For instance: the 2013 Urbit had a shell and a persistent distributed chat – but the shell was mixed in with the kernel, and the chat with the network protocol. As seen from the 2019 Urbit, this is very lame indeed.

The conventional wisdom is to ship your embarrassing "MVP." For several reasons, Urbit occupies a unique strategic position. Urbit just isn't relevant until Urbit is, if not perfect, uniformly excellent. It can't just work. It has to work right. Urbit has to be amazing – which is hardly a useless discipline.

I still did not think it would take five years to make Urbit work right – or to get the resources to make it work right (which only happened in 2018). But founders always delude themselves, or no one would do it.

Urbit is not uniformly excellent quite yet. There are a few medium-sized cleanups in the near-term pipeline. But this is a matter of months, not years. I don't see any unknown unknowns. The adventure isn't over – but the exploration is over.

A clean-slate system software stack, from fundamental interpreter to social network, through typed functional language and deterministic OS, is an enormous architectural journey – so long and winding that it's easy for anyone to get lost in any detail. Isn't that any explorer's first job: not getting lost?

But once the route is marked, there is a second duty: getting out of the way. It's time for surveyors, not explorers, to map, measure and smooth every wrinkle on the map. That's how system software matures. Lines first ripped in one long slash are polished, straightened and refined across years and decades.

And Urbit is too deep and interesting for one technical leader. Every part of it needs its own owner. But others can't build a real sense of ownership while the founder is still around. I'm not even the best engineer on the project; I just got here first.

This codebase is very young and very general; there is a lot of fun left to be had with it; others deserve to have that fun.

I have no successor as "BDFL." Technical leadership passes to Tlon as a company. Urbit is open source and anyone may play, but anyone who wants to catch up to Tlon still has a lot to learn. Not that that should stop them!

I can't make Urbit technically transparent in one speech. But maybe I can shed a little light on the strategy, organization, history and future of the company and the project. It's easier to be frank on the way out.

Tlon, boiling oceans since 2013

First of all: why did we do what we did?

An ambitious system software project can inhabit one of four institutional forms: bigco, startup, academia, or community.

None of these is a fit for a clean-slate system software stack. The startup is the least worst. I'd do it again.

A normal startup lifecycle (Tlon actually got into YC, but declined – this was either cool or lame) looks nothing like a normal system-software lifecycle. Nor is Urbit normal. But while Silicon Valley is absurd, it still fits Marianne Moore's line: "with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers that there is in it after all a place for the genuine."

The less said about big companies and big science, the better. But the choice between startup and community is interesting. Let's talk a little about why Tlon, this corporation, exists, then a little more about what it actually is.

Tlon, from cathedral to bazaar

I used to think I could give Urbit directly to the world – that I could just post the code and an open-source community could take it from there. That'd probably work now, but it's not yet the right thing – and not because nobody wants a revolution.

I've never been an open-source person myself. But the model has fascinated me since I encountered Nethack in the '80s. Now that open-source software is a mature field, we can see what kinds of problems the open-source "bazaar" mode is and isn't good at, versus the corporate "cathedral" mode.

One problem open source isn't good at is creative collaboration on large and novel systems. For example, if we consider the set of people creating Google's new Fuchsia OS, and the set of people contributing npm modules, we see that it's almost impossible to imagine something like Fuchsia as a community effort – but this is not for lack of talent-hours. Imagine a bazaar creating a feature film, and you'll get the picture. (And Fuchsia seems like a fairly traditional OS.)

Why is creative work so hard for bazaars? We could take this as an axiom – but it's worth understanding.

The path from concept to product is an annealing process. Your code starts as a gas and ends as a metal. It must cool gradually under precise control. When parts cool too fast, flaws appear. Where flaws appear, the code must be reheated: ie, rewritten.

Except for ASCII and a few algorithms, Nock, Hoon and Arvo didn't really rely on anything from 20th-century CS. We didn't drop any off-the-shelf parts into the oven; the whole stack is made from gas. So the code in Urbit has been rewritten at least once; the best code has been rewritten four or five times; perhaps some has been rewritten ten, fifteen, even twenty times.

In 2002, I started out with no idea what I was doing. Urbit was interstellar vapor. I did have a decent grounding in 20th century CS, academic and practical. In the '90s I was a grad student in OS at Berkeley, then spent eight years on system software projects (a language, an OS and a browser) in industry. What I wanted, I did not know; what I knew, I did not want.

In a long annealing process, it's important to triage the order in which you solve problems. There are three kinds of problems: problems you can't solve now, problems you don't have to solve now, and hard problems. Unless you postpone anything that isn't a hard but solvable problem, your gas will never turn into steel. There are lots and lots and lots of ways to go nowhere fast.

Somehow it's 2019. Urbit is hot iron under the hammer. It is solid, but not yet hard. It has shape, but can yet be shaped. It is done, but ought to be finished. It is a sword; you don't want to get stabbed with it; it is not Excalibur, the blade to end all blades.

The bazaar is great. But cathedrals still exist for a reason. The challenge for an ambitious system-software project is not whether to choose the cathedral or bazaar model, but when and how to transition from cathedral to bazaar.

A cathedral – the same classic pyramid org-chart no doubt used by the builders of the actual pyramids, or the actual cathedrals – is economically less efficient than a bazaar. Why?

Even on the world's most fun project, working for some dumb boss is no fun. The bazaar succeeds because the project extracts free labor from contributors – not by cheating them, but in exchange for fun, status, experience, etc. But mainly fun, honestly.

Whereas a cathedral costs a giant ton of money. But in exchange, the cathedral gets cohesion – the capacity for intelligent coordinated action. Bazaars can coordinate, but not easily.

Because a cathedral can coordinate, a cathedral can create – acting at a scale above individual action. A bazaar is very useful, but a bazaar does not create. It can grow; it can heal, harden, extend, and expand; but creation requires an individual or a coordinated group.

But a bazaar can get a lot more done, a lot faster and a lot cheaper. So the right starting point for a bazaar is an existing system which is very clear, very final, and very simple. So any new system should be created by a cathedral and perfected by a bazaar. Since these institutions share little or no structure, the transition is by no means straightforward.

Tlon, just a little startup

Tlon is Urbit's little corporate cathedral. It's about 20 people, about 15 of them engineers. Everyone is working on Urbit, but not everyone is writing Hoon; there is client-side work, Ethereum work, etc.

The team is comfortably funded and more than competent. One Tlon engineer is a 10-year, level 6 Google veteran; another is a YC alum; these people are great, but not really outliers. And not to be credentialist – there are plenty of dropouts, too.)

Today, there's almost no part of the Urbit codebase that I still know better than anyone else. There are even design areas that others know better. When we transitioned from Nock 5 to Nock 4, all I contributed was a suggestion. The same for our Ethereum address collection, which our customers absolutely loved.

Who's responsible for growing and maintaining this team? Who's the stone at at the top of the pyramid? Not me: if you gave me a goat to feed, the goat would die. The stone that holds the arch together is Tlon's CEO and my cofounder, Galen Wolfe-Pauly.

Tlon was founded in 2013; Galen led it through its long seed stage, with only a few engineers, to 2018, when he finally secured the resources to do the project justice. (Although way too much of Tlon's energy in 2018 had to go into Ethereum.)

Galen's previous project was the social meta-network Ost. He has an architecture degree from Cooper Union; he is a great designer, a good front-end engineer, and a pretty good surfer. (He also runs the @urbit Twitter.)

Galen sets Tlon's product vision and is responsible for both visual appearance and human experience. Basically, Galen is the Steve Jobs of Urbit, with only two differences: Galen's not an asshole, and Steve wasn't short.

Galen is joined in the new leadership team by Erik Newton (operations, legal) and Anthony Arroyo (product, engineering). Erik used to run a divorce-law firm and still is a relationship coach. Anthony was a grad student in comparative literature and managed engineering prototypes at Applied Minds.

With my departure, Galen is in exclusive control of Tlon and holds the only board seat. Tlon did take seed funding from VCs. But outside investors have never held any management role.

Urbit, in the rear-view mirror

Since I'm not going to talk about Urbit again, let me say a few words that might otherwise go unsaid.

Urbit, a level and neutral platform

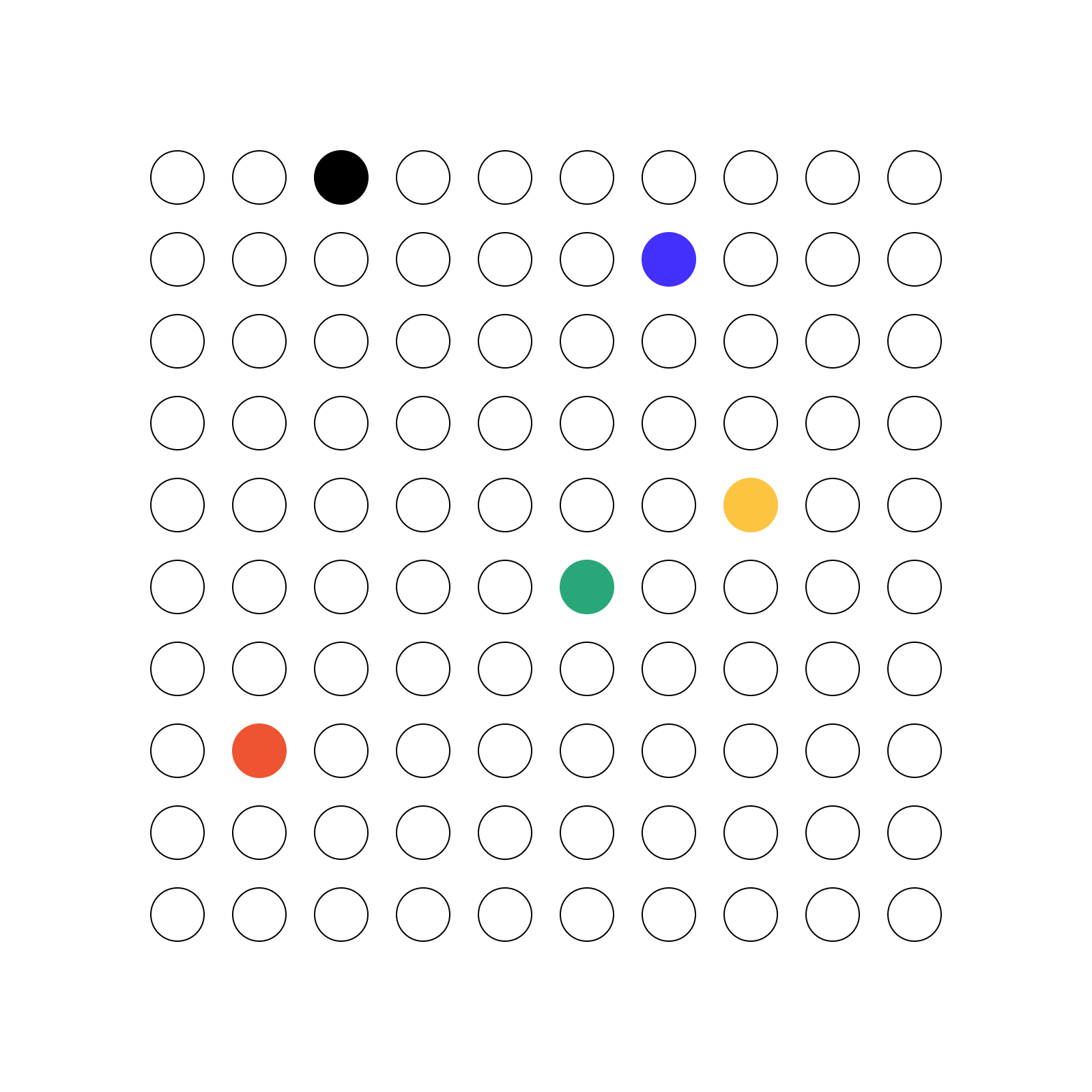

Urbit's distribution and sponsorship hierarchy of galaxies, stars and planets is not designed as a political structure, or even a social structure. The actual social layer is in userspace -- one layer up.

Socially and politically, Urbit is a flat network of planets. Galaxies and stars are plumbing. No one cares which star is your sponsor, any more than your Facebook friends care who your ISP is, or you care what data center Facebook is in.

The sponsorship hierarchy and the senate of galaxies (which can amend Urbit's Ethereum constitution) are technical governance mechanisms. They exist to react to unanticipated technical issues or conflicts (like denial-of-service attacks). Because sponsorship has an escape mechanism, it is not a feudal bond (like your relationship to Facebook).

Urbit is a decentralized network of social networks. No one can regulate it. Urbit is made to blossom into an endless garden of human cultures, each of which must regulate itself, none of which can bother the others. The soil in which these flowers grow must be level and neutral.

Urbit, anything but a fair distribution

Who got those galaxies, anyway?

Urbit has no mining mechanism and needs none. My model was: I own the whole space, since I made it; on the other hand, it's worthless until I find a way to give it away.

In the end, I am probably the only individual with a fair amount of Urbit address space (no galaxies, a few percent of all stars). Tlon plus urbit.org↗ also have about the right amount (slightly less than half). The rest are held by third parties – all of whom have either much more, or much less, than they deserve.

But although the distribution of Urbit space was thoroughly unfair, it was always honest and never corrupt. Everyone who has galaxies or stars did something for Urbit. Some gave a lot of money, some gave a little; some contributed a lot of code, some just showed up. We paid a lawyer by bartering a pair. A bunch went to contest winners who solved a trivial Nock problem in 2010.

What's unfair: the standards changed wildly across time. What's honest: they were always the same across people. Granted, you often had to be in the right place at the right time. This is another problem with life that we can't fix.

Every real system of property is unfair. Who deserves to own Manhattan? Who does own it? If property be not unfair – if it is not the result of respecting past accidents – it is not property at all, but something else. I certainly would not do it this haphazardly again, but the outcome is no tragedy.

When you live in Manhattan, you simply don't worry about who owns it or why; and nor does it matter. Are they Jews? Muslims? Christians? Communists? Italians? You don't care and you don't have to. You know it's basically random and probably unfair. Randomness, even blatant unfairness, creates a kind of neutral, peaceful, even promising urban anonymity.

Property is always and everywhere a kind of amnesty. It says: whatever happened in the past, this is now what is. When we all agree that everyone has what they now have, however they got it, we have a formula for peace. When we say that everyone should have what they deserve, we can never expect everyone to agree – which means we have planted permanent seeds of discord.

And randomness is a virtue – it disrupts hidden patterns. The galaxy owners include famous VCs and total nobodies; a Zen monk and a former Orthodox nun; a blockchain industry leader and a permaculture farmer. If they do have to all agree on something, they should have little to agree on but the truth.

Urbit, a technical report card (January 2019)

As a system-software stack, the fundamental thesis of Urbit is that technical simplicity can flow all the way up to the top of the stack, where it becomes human usability. If we can build a purely functional OS, we can build a zero-maintenance server, which is easy to understand because how it works is simple. With this problem solved – nothing else matters.

Unfortunately, I still have to give Urbit an "incomplete" here. No grade is available, because usability depends on a lot of fit-and-finish issues that are naturally back-loaded. I would still much rather run an Urbit ship than a Mastodon instance. But still, Urbit today can't quite promise zero maintenance.

So we have to look at smaller indicators. One way to get anyone to grade their own work is to ask them for three ways they've succeeded, and three ways they've failed.

Urbit, three battles won

I did once want to be a real computer scientist. Before my expulsion for sordid & disturbing behavior, I was once a 19-year-old PhD student in CS at Berkeley. I even made an embarrassing bet with Raph Levien as to which of us would win the Turing Award – my money is definitely on Raph at this point. You can even go and read my Usenix '93 paper on ASLR-secured RPC, which won Best Student Paper and has like 50 citations.

Well. That whole scene is a bad trip, kids. Avoid it. Also, if you start out as Rimbaud, you might end up as Lebowski. On the other hand, to have any excuse for boiling the ocean, you do have to make some serious CS problems just go away. Here are three.

Validation

20th-century languages underrate the centrality of communication to computing. Their type systems expect all data to live in a single memory forever. They don't consider data serialization and validation to be core competencies of a programming language.

So serialization/validation is handled either ad hoc, or by intermediate data description systems which have inherent impedance mismatches with the language proper. Not only is work done over and over – but most network security breaches exploit seams in custom or complex deserialization and validation code.

In Urbit there is one kind of data, a noun, which is an atom (unsigned integer) or a cell (ordered pair of nouns). There is one serialization model, which maps noun to atom to noun, in a page of code. And a type defines a set of nouns by defining a function of an arbitrary noun, whose range is that set – which means any data type is also its own data validation function.

Idempotence

20th-century computers have two brains: one fast and temporary, the other slow and permanent. When one of these two-brained computers hears a packet, and sends an acknowledgment, that only means the temporary brain heard it. Acks are not end-to-end transactions.

This means you can't write a command protocol where your commands get executed exactly once. You can only choose "at least once" or "at most once." This problem is as ridiculous and frustrating as it sounds.

You can address it in three ways: (a) make all your commands formally idempotent, so that repeating them has no additional effect; (b) insert a layer of stateful middleware — a message queue; (c) be fine with "almost always once." Guess which approach is most popular?

Your Urbit ship has one permanent brain. Its acks are end-to-end transactions — no packet is acknowledged until all its direct effects are finalized. Every message channel is its own message queue. And every message is executed once.

Dependencies

20th-century languages are all at least vaguely based on a formalism from the '30s called the "lambda calculus." The fundamental operation in lambda calculus is variable reduction from name to value. So lambda languages all have a symbol table or environment which binds names to values.

Modern build systems assemble large programs out of small files by reusing this symbol table for global function names, a process called "linking." Unfortunately, linking causes a problem known as "dependency hell," involving baffling, unpredictable upgrade failures. The fundamental problem is the "diamond dependency" — when a build requires two different versions of one symbol.

Urbit does not use the lambda calculus, an environment or symbol table, or linking. Because it pushes name resolution out of the fundamental interpreter and up into the language, it can play many more namespace juggling tricks. And its build system has no trouble including multiple versions of the same library.

Urbit, three battles unwon

As I mentioned earlier, triage is essential on any long journey. You have to keep moving forward, even when you have no idea where you're going – which means attacking the hardest problems you can solve right now.

Unfortunately, this is a different standard than the usual rule for shipping a product: solve the most important problems first. This principle of triage is a general case of Knuth's apothegm against premature optimization. Urbit, in fact, was absurdly slow for a long time, but after a couple of engineer-months of focused optimization it seems fine now.

But there are other areas where Urbit today is surprisingly weak. All look careless, but all are the result of careful triage. When you find a weakness due to triage, you may think you are judging Urbit's quality. You are just judging its maturity – which doesn't make your judgment wrong, of course.

Opacity

Urbit's notorious opacity is the problem that makes people complain the most. It's not an unwarranted complaint.

At least, it's not all an unwarranted complaint. Part of the complaint is just about novelty. Novelty is of course inherent in any clean-slate stack. I do regret making 0 true and 1 false. On every other count, however, I offer all critics of Urbit's novelty none but the most vulgar gesture.

But novelty is not the only problem. Urbit's external documentation has gotten much better in 2018 – in particular, it's now much easier to learn the language. Its internal documentation, and general code quality, remains at best poor to average. Worse: the worst code is the oldest, deepest code, which is also the most fundamental. Not only is it not commented, it is full of cryptic, meaningless names.

There is now a new style guide, which should enable all reference documentation to migrate into the codebase. But this style guide is so new that none of the codebase complies with it. The guide demands "space-rated" code that documents every variable and every line – and almost none of the codebase is space-rated.

Urbit's internal opacity persists for two reasons, one good and one bad. The bad reason is just laziness. The good reason is justified fear of premature explanation, which like premature optimization ruins the annealing process.

When you don't know exactly what you're doing, preserve as much ambiguity as possible. For example, a name that means something is a commitment to one specific explanation; a name that means nothing is no commitment at all. A cryptic name is productive procrastination; it lets the hard problem of naming get solved later, and hence better.

Impermanence

Your Urbit ship needs to be permanent. That means it doesn't lose data, sink, or get wedged, or rot. It's not complicated. I wish Urbit today could make this promise, but it can't.

There are are two problems here: short-term permanence and long-term permanence. Short-term permanence means your ship can't fail or lose data except via OS or hardware failure. Long-term permanence means you can put your ship on a USB stick in a box for 50 years, or 100, or 500, and when you turn it on in a modern interpreter it will upgrade itself and work fine.

There aren't any significant structural obstacles to each of these milestones. But we can't claim them yet. We haven't really even worried about them. This is another triage case: in this case, the issue is premature reliability.

Permanence also includes security. Except for the on-chain PKI, in which case you're trusting Ethereum, you shouldn't yet trust Urbit's security at all. Sorry!

Duplication

Triage can procrastinate in the other direction. It can skip problems that are too hard to solve. When you procrastinate, always come back – in this case, when the problem is easier. Here's one way Urbit has skipped a problem that was too hard.

Urbit, as you may recall, is a single-level store. It has only one brain. And yet, we resisted the natural unification of documents and applications and secrets that a one-brained computer obviously suggests.

Instead, Urbit today is built more the Unix way (if not the Windows way). It has separate subsystems for tracking and updating these three kinds of data. This was my design. Like Urbit's opacity or impermanence, this was always obviously lame.

Why do it the lame way? Because, before understanding the union of these problems, we had to understand each problem by itself. We didn't – not even close.

No one else ever built a purely functional operating system. No one is going to go straight from zero to the right thing. You have to solve a hard problem, learn from it, and do it again.

Now that the team has built and used the specialized subsystems, it's probably time to go ahead and generalize. The problem now strikes me as almost straightforward. The constraints are clear and so are the tools. None of this was true a year ago.

On the low end, triage keeps you moving forward by stopping you from wasting time on easy problems. On the high end, triage keeps you moving forward by keeping you from leaping too far ahead, and falling down an impossible rathole.

Further reading

What will I do personally? I'll spend more time with my kids. I'll finish reading my 1911 Britannica – I am only on the B's. I have no other long-term plans.

But I won't be back to Urbit. I am leaving not just the project but the field – no less than Satoshi, or Everett, or Rimbaud. Will Satoshi weigh in on the next Bitcoin Cash fork? Did Rimbaud fly back from Ethiopia for his book-release tour? (Did anyone want him back?) It's not so bad to be a middle-aged Rimbaud.

Is there more to say? Of course, but not in prose. Read Bunting's Chomei at Toyama and Notes on a Fly-Leaf; Cavafy's Il Gran Rifiuto, Keeley & Sherrard translation; Canto XV of the Inferno, Pinsky translation. You might learn something.

Apologies and acknowledgments

I apologize to anyone who has too little Urbit space. I refuse to guilt-trip anyone who has too much.

I appreciate my friends by not naming them. I disarm my enemies by inviting them to lunch – but only if they come unarmed.

I thank everyone who has ever worked on Urbit and everyone who will work on it in the future; our backers, great and small; my cofounder, Galen, and his family; my parents, wife and kids.